Bilingualism protects against cognitive decline

But who counts as bilingual? And is it still worth learning a new language as an adult?

In a recent issue of the New Scientist magazine,

reported on the link between bilingualism and delaying the onset of dementia. The article sparked my interest because, as a speaker of more than one language, this could spell good news for my ageing brain.So how did scientists make the connection between bilingualism and dementia? Who counts as bilingual? And based on the science, is it still worth picking up a new language as an adult?

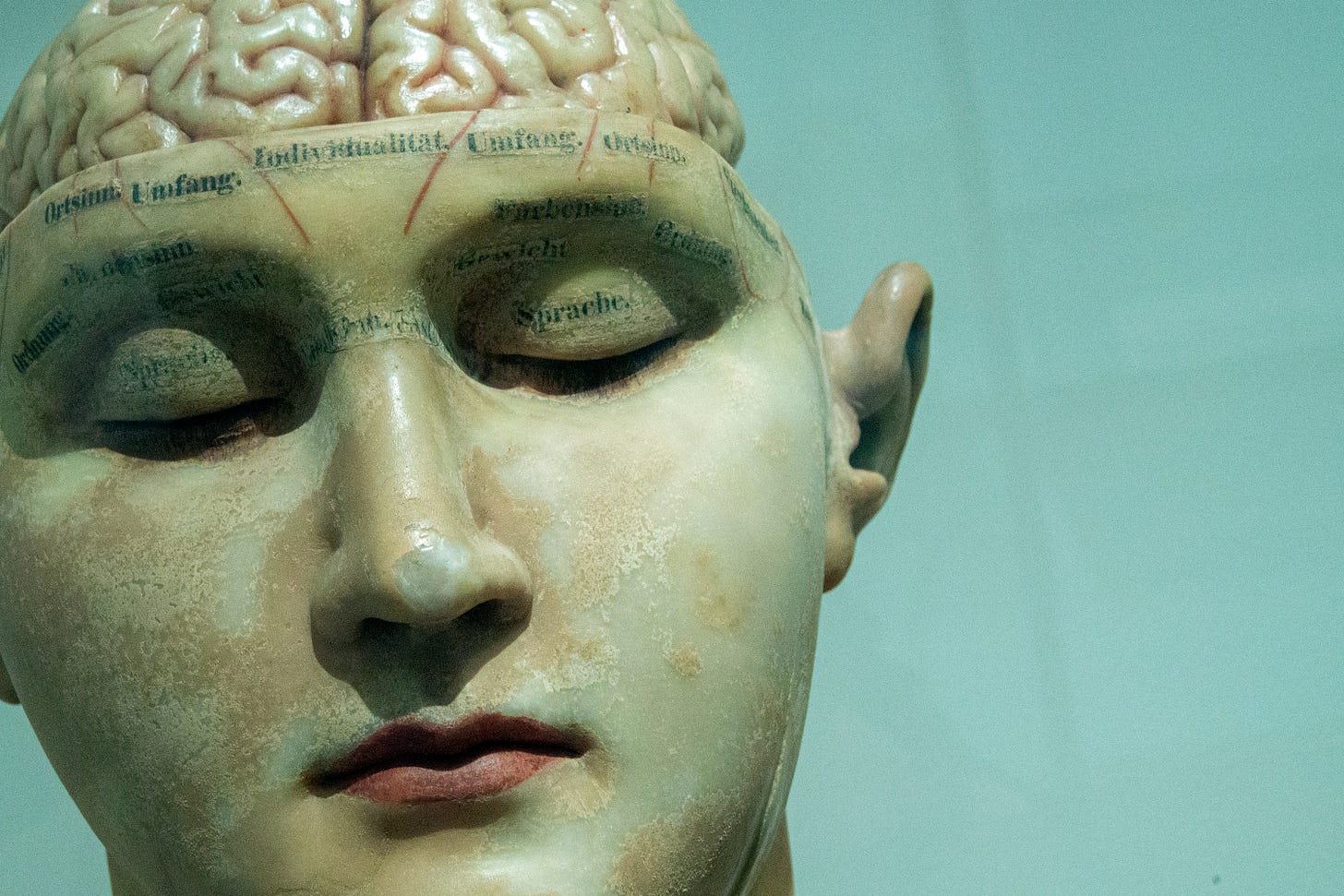

The bilingual brain

One way of finding out how speaking a second language might affect the brain is to study the differences between monolingual and bilingual speakers in terms of what their physical brains look like, and how the various regions of the brain associated with language might differ.

Interestingly, learning a second language changes your brain. This is called neuroplasticity, the brain's ability to reorganise and rewire its neural connections.

As a bilingual speaker, your brain is ‘working out’ a lot more when switching between languages, and this constant workout leads to a higher density of the grey matter that contains most of the brain’s neurons and synapses.*

For a short illustration, watch this animated TED Talk by Mia Nacamulli on the benefits of the bilingual brain:

So, speaking a second language is not only great fun and opens the door to new experiences and cultures, it also helps to keep our brain fighting fit. And this brain fitness turns out to be crucial in helping us delay cognitive decline.

The link between bilingualism and dementia

But how can we know that a fitter bilingual brain could help us specifically in delaying the onset of dementia? The answer lies, at least in parts, in data.

A number of studies have dived into data archives of dementia patients to see if there is a link between bilingualism and dementia.

Looking at retrospective data, studies have shown that bilingual patients developed dementia 4-5 years later than monolingual patients.

A study by Ellen Bialystok in 2007, for example, compared the records of 228 monolingual and bilingual patients referred to a memory clinic and found that bilingual patients showed symptoms of dementia on average four years later than monolingual patients. Another study by Suvarna Alladi in 2013 with 648 patients showed similar results: bilingual patients developed dementia 4.5 years later than the monolingual ones.**

These findings give us a good clue, from a statistical perspective looking back in time, that bilingualism positively contributes to delaying the onset of dementia.

My hippocampus is bigger than yours

So, what’s going on in bilingual brains that helps to delay the onset of dementia? That’s exactly what Kristina Coulter and Natalie A. Phillips set out to investigate in 2023.

They studied brain resilience in a group of older adults. A mix of monolingual and bilingual speakers, the participants included people who were either cognitively unimpaired, showed mild cognitive impairment or had been officially diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease, a form of dementia.

Using surface-based morphometry (a structural neuroimaging technique), they measured the thickness of the cerebral cortex (the outer layer of the brain’s surface) and the volume of language-related and Alzheimer’s Disease-related brain regions.

Interestingly, they didn’t find any evidence of physical differences in the language-related regions of the brain, but they did stumble across a difference in the participants’ hippocampus.

This is particularly fascinating because the hippocampus isn’t a language-related area of the brain. It’s actually a part of our brain that’s responsible for learning and memory. It is also one of the first areas of the brain that is affected in dementia.

The hippocampus is responsible for consolidating short-term memories into long-term memory. That’s why dementia patients tend to have a terrific long-term memory, but can’t remember what happened yesterday, or sometimes even an hour ago.

The study found that in healthy, cognitively unimpaired participants – both monolingual and bilingual – the hippocampal volume was the same.

In dementia patients, however, they found a difference. While the hippocampus showed signs of decline in monolingual dementia patients, bilingual patients showed no such decline.

Bilingualism contributes to brain maintenance, meaning dementia patients can enjoy a better quality of life for longer.

These findings suggest that, compared to the monolingual brain, the bilingual brain is better able to prevent the hippocampus from deteriorating when dementia sets in. In other words, a bilingual speaker is able to maintain their normal cognitive function for longer.

Dementia is a horrible disease that robs people of their intellectual autonomy and their ability to live independently. It has a profound impact on the patient as well as their loved ones. If speaking another language can help us fend off the symptoms of dementia for a few more years and maintain a good quality of life for longer, then that has to be good news, right?

Who counts as bilingual?

You might be asking yourself if any of this information is useful for you. If you speak more than one language, does it necessarily mean that your brain is going to be able to fend off dementia for longer? Just how bilingual do you need to be to reap the cognitive benefits?

Anyone who speaks a second language (or more) will know that defining bilingualism is no straightforward task. Does a person need to speak two languages equally well to be classed as bilingual? What about usage? Is it enough to have learnt and spoken both languages at some point in your life? Or do they need to actively use both languages?

Bilingualism is an ambiguous concept. Even in scientific research, the concept is not universally defined and seems to vary across studies. Let’s look at a few aspects of bilingualism: age of second language acquisition, language use, and number of languages spoken.

Age of second language acquisition

We do know that neuroplasticity is greatest in childhood, and when children learn a second language, they tend to use both hemispheres of the brain, whereas adults mainly use the right hemisphere. This means that learning new languages in childhood yields the biggest benefits in terms of building up brain resilience.

Neuroplasticity does decline as we get older, but it doesn’t stop completely either. So even though adult language learning might not have as dramatic an effect on the brain as learning in childhood, it definitely still contributes to combating cognitive decline.

Language use

In 2020, Marco Calabria and his team carried out a study to show that, actually, it’s not enough to just know two languages. They tested patients with different degrees of language experience and usage, and concluded that it’s active bilingualism that is crucial in delaying the onset of cognitive impairment.

So, learning a language at school and then never using it again might not be enough to truly protect the brain. The study points towards the active use of two languages and the frequent switching between them as being the biggest contributor to brain resilience.

This might also be an interesting point for people who, like me, don’t live in their native country. My native language is German, but I haven’t lived in Germany since the start of the millennium when I moved to the UK. My German language use is typically limited to speaking with family and friends back home as well as some German friends here in Portugal, but the majority of the time I speak (and think) in English. On the other hand, now that I live in Portugal, I’m learning Portuguese and speak it fairly frequently. I feel like I’m losing some of my German, but gaining in Portuguese instead, although I don’t speak it as proficiently as German. Does that make me an active bilingual? This is just one example of how messy bilingualism is as a concept, as experiences tend to differ hugely from one person to the next.

Number of languages spoken

Finally, does it matter how many languages you speak? Does the brain get more resilient with each language you add? It would seem so. Some studies even suggest that at least 3 or 4 languages are needed to protect against cognitive decline. Simply put, the harder your brain has to work out, the more resilient it becomes.

Does the definition of bilingualism matter?

The different papers I read through in preparation for this article cited studies from all over the world. One study looked at French and English bilinguals in Canada, while another looked at Spanish and Catalan bilinguals in the city of Barcelona, Spain. While yet another looked at multilingualism in India. These are countries with vastly different cultural, socio-economic and immigration backgrounds. How languages are used in daily life is bound to differ dramatically between these countries, as well as between individuals.

Just as an example, a bilingual speaker from Barcelona who switches constantly between Catalan and Spanish as part of their day-to-day life might possess a very different second language proficiency than a French Canadian speaker from Québec who only sometimes switches to English. Yet both are classed as bilingual.

We also need to bear in mind that, at least in some studies, participants self-reported on their language abilities (as opposed to everyone being tested against a unified benchmark). This means we’re relying on how individuals define bilingualism and language proficiency, which can vary wildly from one person to another.

Ultimately though, for those of us who are fortunate to already speak more than one language, it doesn’t really matter if, in the eyes of science, we’re classed as bilinguals.

The simple fact that we speak another language is providing us with a cognitive advantage. And perhaps spurs us on to make more regular use of the languages we know.

Is it still worth learning a new language later in life?

If you’ve not yet mastered a second language, or you’re keen to add another one to your repertoire, then it’s never too late to get started. Stimulating the adult brain, particularly in later life, plays a hugely positive role in maintaining cognitive function.

Intuitively, we know that we need to keep active both physically and mentally to keep our bodies and minds fit as we grow older. Science backs that up. Studies have shown that when older people regularly engage in intellectual activities like reading books, doing crossword puzzles, going to museums and so on, it helps to delay and even reduce the occurrence of cognitive problems.

One study of older adults over the age of 75 showed that those who did crossword puzzles four days per week had a 47% lower risk of developing dementia compared to those who only did a crossword puzzle once a week. And that’s just doing puzzles.

Learning a new language is a fantastic boost for the brain – at any age.

Learning a new language is an even more supercharged way of stimulating the brain because it engages a larger brain network than doing a puzzle or reading a book. So much so, that some scientists suggest language learning in older adults as cognitive therapy. In other words, language learning is the perfect all-round workout for our brain.

*This is very much a simplified explanation. For more of a deep dive into which regions of the brain change when learning a new language, I suggest reading Growth of language-related brain areas after foreign language learning.

** Scientists have also retrospectively looked at statistical data available across countries to see if there is a correlation between bilingualism and dementia. They compared data from countries with bilingual and multilingual speakers to countries where people only use one language to communicate. And there is “considerable evidence for lower rates of senile dementia as the mean number of languages spoken increases from one to two”. But the data is somewhat messy because “there is no consistent set of global data on either the degree of monolingualism or the age of onset of Alzheimer’s Disease symptoms per country.” There is no absolute linguistic homogeneity across the population of a country. Even within a bilingual country like Canada, there will be people who are monolingual. And conversely, there are plenty of bilingual and multilingual people living in a monolingual country like Germany. And of course, data only tends to exist for people who have actually been diagnosed with dementia and who have been recorded in the system.

Bilingualism is pure magic. As a Spanish linguist raising three little kids in Ireland, I probably enjoy their language adventures way more than is socially acceptable.

It's a fascinating topic. I remember, a long time ago, reading that interpreter brains and London taxi driver brains were similar, since the taxi drivers had done the 'knowledge' and the two hemispheres could process data more or less independently (I'll have to try and find the study again now).

In the meantime, here's to another of the many benefits of multilingual minds!